I wake at 3 a.m. My mind is cycling through my responsibilities for the next month. What if I can’t get it all done?

One of my kids has a fever and a cough that sounds bad. We know people who are in the hospital with pneumonia. What if this gets worse?

My girlfriend and I had a big fight and haven’t talked in a day. What if we break up and I can’t find anyone else?

I’ve lived through all three of these scenarios. All three are instances of worry, which is the next enemy of contentment in the lineup. Given that counselors call anxiety the common cold of mental health problems, you’ve likely faced worry too.

Meditating on fear

Worry is a subspecies of fear. Specifically, worry is meditating in fear on an imagined future. If being in the same room with a tiger triggers fear, worry is imagining that there might be a tiger in the next room. While we might not think this way when we’re worrying, all worries can be phrased as “What if?” questions.

Health worries: What if I don’t get better?

Relational worries: What if this relationship breaks?

Financial worries: What if I lose this money?

Worries about the world: What if that disaster happens?

And worry isn’t a one-time moment of fear: it meditates on the fear, gnawing on it like a dog chewing a bone. It lays awake for an hour. It broods through the date. It greets us in the morning with, “Now, where did we leave off?”

The meditation is also significant, because worry tends to stew in fear instead of act on it. If I’m afraid a tree might fall on my house, that fear can lead me to action that mitigates the threat: having the tree cut down. Healthy fear is designed to lead us to action. Worry, though, ruminates helplessly on the fear.

Hag-ridden by the future

Worry isn’t necessarily sinful, like envy. Christian physicians of the soul through the centuries have classed it more as an affliction, which is a besetting problem that can lead to sin. And it’s certainly an undesirable condition. Paul commanded the Philippians, “Do not be anxious about anything” (Philippians 4:6). And hear Jesus’ exhortation:

“Therefore I tell you, do not be anxious about your life, what you will eat, nor about your body, what you will put on. For life is more than food, and the body more than clothing. Consider the ravens: they neither sow nor reap, they have neither storehouse nor barn, and yet God feeds them. Of how much more value are you than the birds! And which of you by being anxious can add a single hour to his span of life? If then you are not able to do as small a thing as that, why are you anxious about the rest? Consider the lilies, how they grow: they neither toil nor spin, yet I tell you, even Solomon in all his glory was not arrayed like one of these. But if God so clothes the grass, which is alive in the field today, and tomorrow is thrown into the oven, how much more will he clothe you, O you of little faith! And do not seek what you are to eat and what you are to drink, nor be worried. For all the nations of the world seek after these things, and your Father knows that you need them. Instead, seek his kingdom, and these things will be added to you.” (Luke 12:22-31)

What makes worry an undesirable state? In brief:

Worry reflects a lack of trust in God. While short-term fear can lead us to God, the long-term meditation of worry draws us away from him. It acts as if the fear is bigger than God, rather than trusting that God is bigger than our fear.

Worry eclipses worship. Related to the first, worry sets our fear up as the most important thing in our minds. It governs our thoughts, emotions, and actions, which should be devoted to God first.

Worry hinders love. If worry isn’t a sin of commission, it leads us to sins of omission. It saps energy and time that could be given to loving God and loving others. We’re designed to “seek [God’s] kingdom,” as Jesus said; worry burns those resources of time and attention for an imagined fear.

As usual, CS Lewis has something brilliant to say here. In The Screwtape Letters, which imagines a senior demon advising a junior one on how to tempt his “patient” toward hell, he vividly illustrates the power of worry to hinder us in the present:

It is far better to make them live in the Future. Biological necessity makes all their passions point in that direction already, so that thought about the Future inflames hope and fear. Also, it is unknown to them, so that in making them think about it we make them think of unrealities.

…

We want a man hag-ridden by the Future — haunted by visions of an imminent heaven or hell upon earth — ready to break the Enemy’s commands in the present if by so doing we make him think he can attain the one or avert the other — dependent for his faith on the success or failure of schemes whose end he will not live to see. We want a whole race perpetually in pursuit of the rainbow’s end, never honest, nor kind, nor happy now, but always using as mere fuel wherewith to heap the altar of the future every real gift which is offered them in the Present.

Fighting worry

So how do we fight worry?1

1. Turn fears into prayers.

I quoted half of Paul’s exhortation on anxiety above; here it is in full:

The Lord is at hand; do not be anxious about anything, but in everything by prayer and supplication with thanksgiving let your requests be made known to God. And the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will guard your hearts and your minds in Christ Jesus.

Paul frames the command against fear with a reminder of God’s nearness, both existential (he’s present with us now) and eschatological (his kingdom is breaking into this one). Because of that, Paul says, we should turn our fears into prayers, handing them over to God. As we do – as we develop that mental habit – we’ll come more and more to remember God’s closeness, God’s power, and God’s goodness, in such a way that “the peace of God … will guard [our] hearts and minds.” Worry forgets that God is sovereign and good; prayer reminds us of those truths.

2. Meditate on God’s goodness.

Fight meditation with meditation. Paul adds “thanksgiving” to his anti-worry prayer regimen. Thanksgiving is reflecting on God’s goodness as shown by his gifts. Thanksgiving and worship, which is reflecting on God’s inherent goodness, can displace worry in our minds by reminding us of the God who is greater than every fear. Just like filling your belly with a healthy meal can help you want unhealthy snacks less, filling your mind with reminders of God’s sovereign goodness can help you be less inclined to meditate on imagined fears.

3. Seek God’s kingdom in the present.

Jesus contrasted worry with, “Seek God’s kingdom,” which means, “pursue what is right.” Lewis expounds on this:

[God’s] ideal is a man who, having worked all day for the good of posterity (if that is his vocation), washes his mind of the whole subject, commits [his concern about the future] to Heaven, and returns at once to the patience or gratitude demanded by the moment that is passing over him.

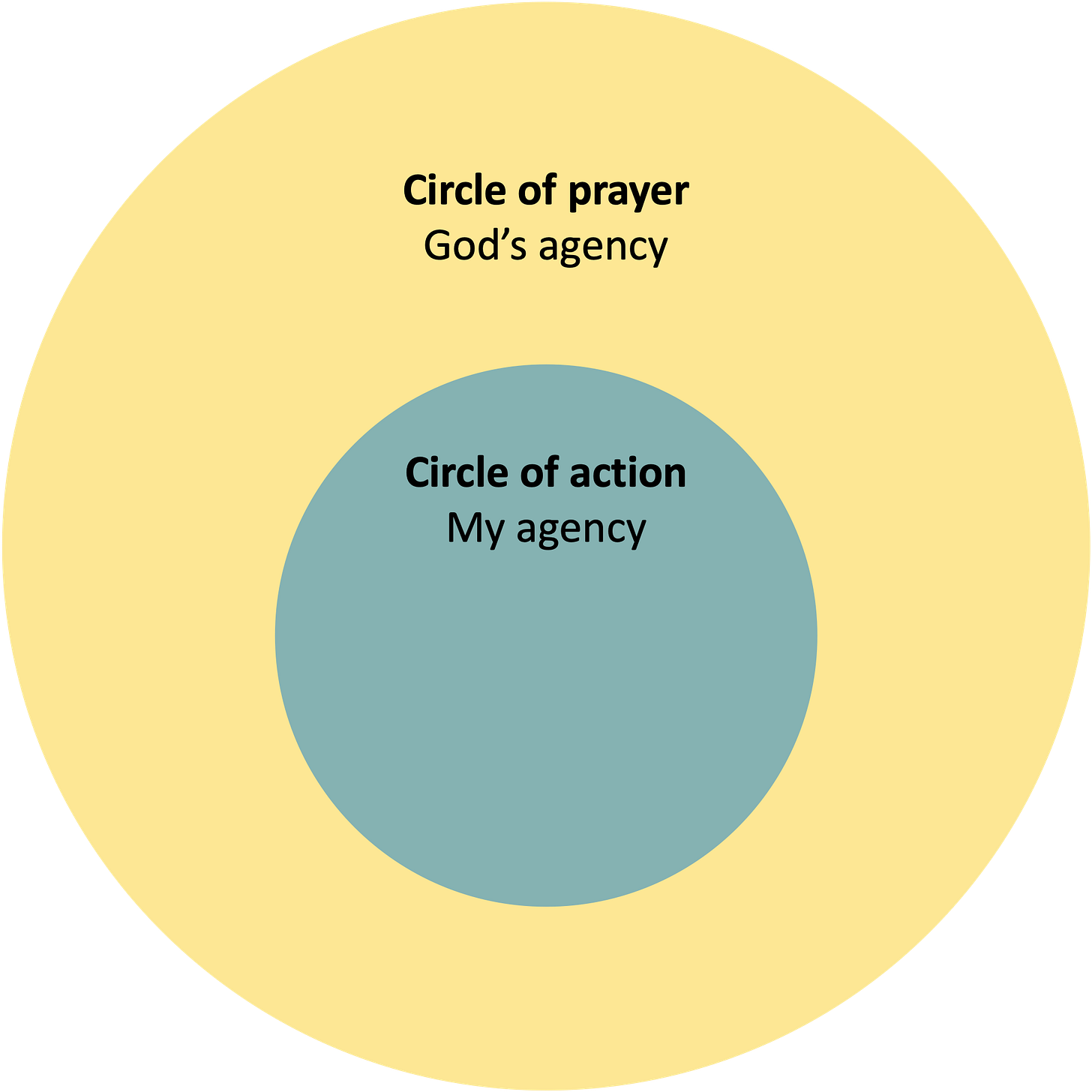

Worry takes us out of the present, which is the only “time” in which we can take meaningful action. To use parlance from modern therapy, it saps our agency, which creates a vicious cycle of stress/anxiety and further diminishing agency.

But if we can entrust the things out of our control to God through prayer and focus on the good things we can do in the moment, we’ll find ourselves in a virtuous cycle of both decreasing worry and increasing meaningful action in the world.

Anxiety, which gives rise to worries, may sometimes have a biological origin and may be helped by intensive therapy or by medication. This counsel isn’t meant to discount those options; but whether your worry requires them or not, these practices will help you in the fight.

Wisdom for life!