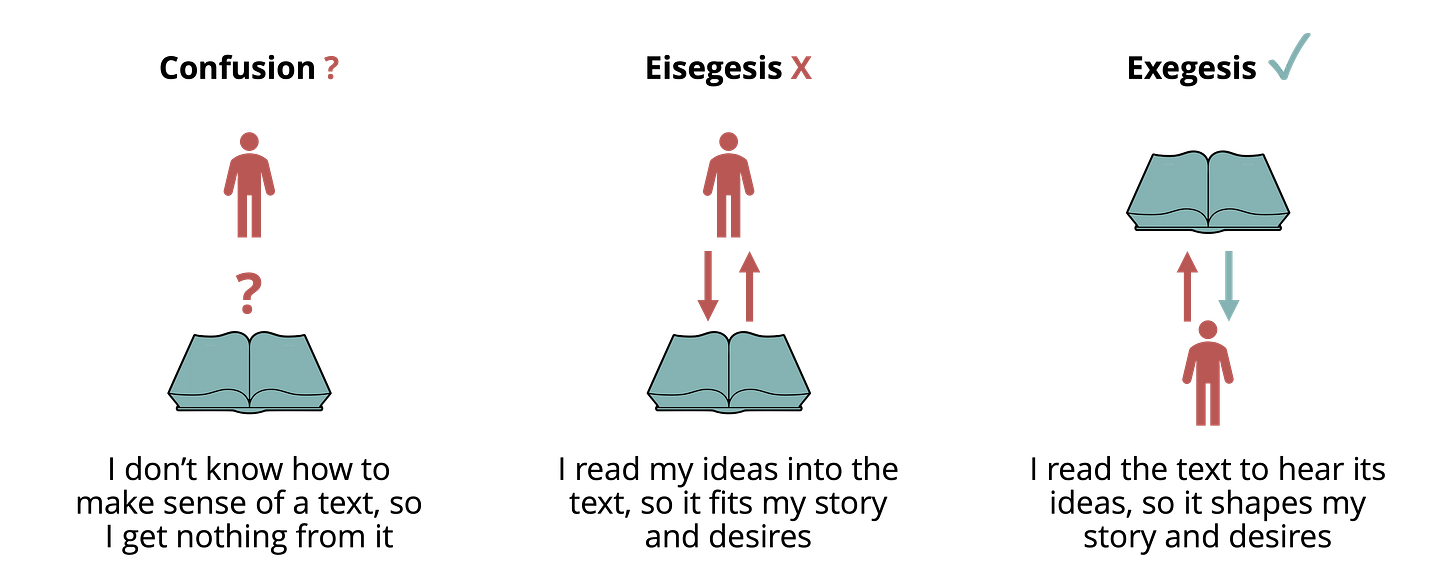

Of the “roots of meditation,” living is the most important, because the biblical text is meant to change how we live. But we begin with the root of learning, because learning ensures we hear the voice of the Scriptures rightly: to hear what it’s saying, rather than just our own ideas (or to hear nothing because we can’t make sense of it).

For example, let’s take Psalm 16:11 – “You make known to me the path of life; in your presence is fullness of joy; at your right hand are pleasures forevermore.”

A lack of learning might just lead me to say, “What?” To have no idea what the path of life is, how there’s fullness of joy in God’s presence (wherever that is), or what kinds of pleasures are at his right hand. If a lack of learning leads to confusion, I won’t really be able to live from the text, because I won’t know how I’m supposed to live.

A lack of learning might also lead me to only read my own ideas into the text. I might have my own idea of what the path of life is, and assume that God’s job is to help me get that McMansion. The technical term for reading into a text just want I want it to say is eisegesis.

The goal of learning

But proper learning allows me to come to a text – especially a text of Scripture – and hear what it has to say. Rather than confusion or just imposing my own ideas on the Bible, learning helps me understand what the Bible says and be shaped by its voice instead of making it dance to mine. It would lead me to discover that “the path of life” is not just God’s will, but ultimately Jesus himself, “the way, the truth, and the life” (John 14:6), and that “pleasures forevermore” include every wonderful promise of the new creation: eternal life on a restored earth in a glorified physical body, beyond the sorrows of pain and evil, in the company of God himself and every other person who has lived by faith in him.

This type of reading, “reading out” what’s actually in a text, is called exegesis.

So what does it mean to read a text – especially the text of Scripture – rightly?

Here’s a general definition for when we have learned a text:

We have “learned a text” when we can summarize what an author is saying and doing with their words.

It’s important to note that words aren’t just for saying – imparting information – they’re for doing – taking action in the world as well. If my wife leaves me a note saying, “Gwyn’s piano lesson is at four,” it’s not enough for me just to understand what the individual words mean, or even to grasp the information that my daughter Gwyn should be studying piano at four. Is my wife telling me that she is taking Gwyn to piano at four? Is she asking me to take Gwyn to piano? True understanding will take place when I know what my wife is trying to do with her communication (and what she expects me to do in response).

Modern communication theory has terms that help us break down each of these parts of a communicative act. They ain’t the purtiest words, but they’re helpful:

A locution is the statement itself (“Gwyn’s lesson is at four.”).

The illocutionary force of the statement is the action I’m trying to accomplish with it (a reminder to take Gwyn to her lesson on time).

The perlocutionary effect of the statement is the desired outcome of the action (I remember to take Gwyn to her lesson).

Distinguishing the terms like this helps us see not just the importance of grasping meaning – what the author/speaker intended for their communication – but also how communication is an action that is often designed to produce change in the world. The table below shows that simple communicative act, plus another one from Scripture that’s more complex:

If we believe the Scriptures are simultaneously coauthored by their human writers and by God (to be discussed in the future!), we summarize learning the Scriptures this way:

Learning means summarizing what the human and divine authors are saying and doing with the words of a text of Scripture (its illocutionary force), and what a reader should do in response (its perlocutionary effect).

This doesn’t have to be just one thing – as we saw, even a statement as brief as John’s can be doing more than one thing – but as long as we’re confident that we understand something of what the authors are doing, we can say we’ve learned from a text.

The process of learning

How do we learn about a text, then? What does this look like in practice?

I’ll categorize my recommendations under a few headings, and then give some practical tips/resources.

A. Connect to what I know (or might know) already

Charlotte Mason, the British educator and educational philosopher, called education “the science of relations” – by which she meant, education is the process of seeing how different things are related to or connected with one another. She also meant that the more we learn to see the connections between different subjects, the more fruitful our education is.

The first task of learning, especially learning about a passage of Scripture, is connecting it to what I know or think I know already. If we believe not only that a single book of Scripture (like 1 John), but the entire canon of Scripture and the entire body of Christian thought called “Christian theology” are ultimately unified, then placing a given text in its context in those worlds might help us understand it.

(Note: if you follow the “I notice, I wonder, this reminds me” reading method, you’ll have started this step already!)

Practically, consider questions like:

Is there context from this passage’s chapter or book that informs my question (like what John does with “light” in 1 John 1)?

Where does this passage fit in the big story/drama of the Bible, and does that change what it would mean for me today? (see Sabbath, cleanliness laws, slavery, etc)

Are there other passages of Scripture or theological truths that should inform my understanding of what’s going on here?

Are there other passages of Scripture that confront this moral choice / question of wisdom, and if so how do those resolve?

Are there any images, illustrations, or stories that help me understand this in a more concrete way?

Simply writing out what I know or might know about a question might lead me to “learn” something I kind of knew before, or make a connection that I just hadn’t seen yet.

Side note: I mentioned this in “It’s All in the Roots,” but one beauty of this kind of thinking is that learning now makes future learning easier. The more we learn, the thicker our “natural knowledge base” for future learning will be, and the more fruitfully we’ll be able to make connections when we’re working with new information.

B. Gather information

I may find that I just don’t have the information needed to learn about a text on my own. In that instance, the root of learning will look like going to look for new knowledge. Specifically, I might go looking for:

The definition of a Greek or Hebrew word, or other places that word is used

Historical information to help me understand a reference to a person, place, or event

Theological resources to integrate a passage into the broader system of Christian thought

Commentaries on a passage where other scholars help me understand it

Devotional writings or sermons that apply the principles of a passage to daily life

My personal go-to for this is a good study Bible, and specifically the ESV Study Bible from Crossway. A good study Bible has several helpful tools:

Brief introductions to each book of the Bible that give some context, big themes, etc.

Cross-references to other passages of Scripture that might inform one passage’s meaning

Commentary notes that explain some of the challenging parts of a text

Historical and theological essays on topics that might inform a given question

Obviously you can go way, WAY deeper into this stuff with full commentaries, concordances, etc., and sometimes that’s beneficial. But practically, a study Bible usually gets you enough to learn and go.

C. Summarize what I’ve learned

CS Lewis said somewhere that seminaries teach Latin and Greek, but not enough English – that no-one should be allowed to graduate seminary until they can go down to the docks and give a day-laborer a reasonable understanding of the Trinity.

Potential wisdom of that approach aside, the principle underneath it is that we haven’t learned something until we can paraphrase or translate it. Simply remembering the words we read – even memorizing them in perfect sequence – isn’t necessarily understanding. Summarizing what I think I’ve learned, even in a sentence or a brief paragraph, is a way of “teaching” it to myself, or re-articulating the fruit of my studies.

Photo by Elijah Hail on Unsplash