Learning: The Grand Drama

How the unfolding drama of redemption helps us make sense of Scripture

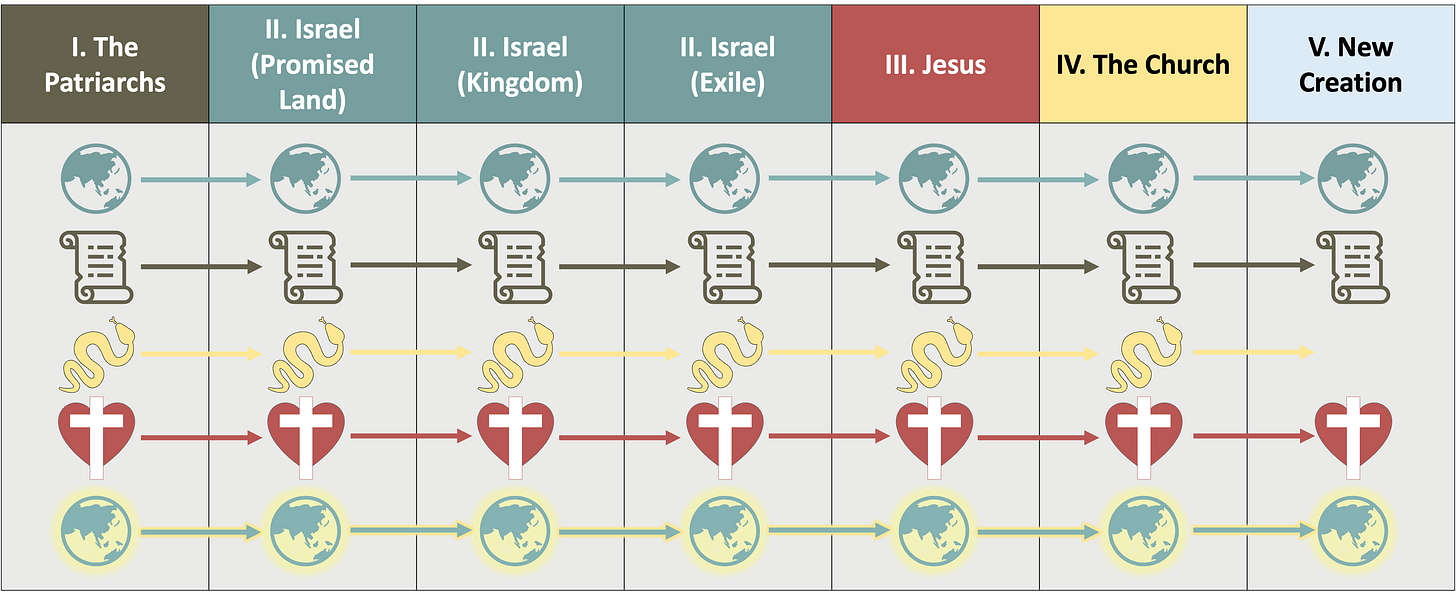

In our last piece, we looked at the grand themes of the Bible that both outline its overarching story and also cycle through each part of the story. Reading for the themes of Creation, Covenant, Fall, Redemption, and New Creation can help us make sense of a passage by seeing what particular drama or tension is playing out.

But while these themes do make one “big story” that starts with the creation of the world and “ends” (if that’s the right word for the beginning of eternity) with its new creation, God has unfolded his plan in a series of “chapters” or “acts[1]” that develop through time. While there is continuity from, say, Abraham, through a Hebrew farmer in the land of Canaan, through a Jewish woman in exile in Babylon, to a Christian today – we’re all part of the same drama – our roles are not identical, because God’s plan has been expressed in a unique form in each of those eras. That unfolding drama is why we don’t set up altars and circumcise our households like Abraham, or why we don’t keep kosher and follow yearly festivals in Jerusalem like a faithful Hebrew in King David’s day. In each act of redemptive history, as we call it, God is the same and his fundamental will for human beings is the same, but the terms by which that will is enacted change.

Just as a Shakespeare play is written in five acts, with Act 3 as the climax, the drama told the Bible can be conceived in five acts. In each one, the same fundamental drama develops and unfolds in particular ways, which leads to particular opportunities and challenges for God’s people.

Here it is, with each book of the Bible fitted as accurately as I know it into the acts:

Let’s see how this plays out.

With the Creation, God has unique, fairly personal relationships with a small set of families – Noah, then Abraham and his children. He makes covenants with them and promises them the “creation” of a permanent home one day, as well as other blessings that will impact the entire world (Genesis 12:3), but their relationship with him is largely a matter of worship, obedience, and trust in future promises.

With Israel, God “creates” the nation by redeeming them from slavery in Egypt and making a new covenant with them through Moses (see Exodus 19 and 20). This covenant is meant to create a political-religious-ethnic nation in one specific place – the land of Canaan – and to govern every aspect of its life. God’s relationship with his people develops through the institution of a monarchy and through the exile and return, but the same basic relationship holds through those changes. All of these books look back to that original covenant given through Moses; and they begin to look forward to God’s promise to create a “new covenant,” or a new way of relating to the world.

When Jesus comes into the world, he both grounds his ministry in the drama of the covenant with Israel, and also says he’s creating a new kind of relationship between God and humanity. That’s why he sometimes seems like he’s upholding it (Matthew 5:17-19), and sometimes seems like he’s establishing something new (Matthew 7:24-29). His act culminates in the Crucifixion – which seems like the ultimate victory of the Fall over God himself – and the Resurrection, which ties together both Redemption and New Creation in the creation of a new humanity in himself.

After Jesus ascends to heaven (Acts 1:6-11), the Holy Spirit, who “hovered over the face of the waters” in the original creation (Genesis 1:3), comes to create a new people of God: the Church (Acts 2). The Church is both continuous with the people who trusted God in the past, from Adam through Moses, David, and onward; and new, because God has set new terms for our relationship that aren’t confined to one place, one nation, or the religious structure of sacrifice and Temple. The new covenant has begun, and we now live in the ongoing drama of facing the effects of the Fall – in ourselves and in in our world – and participating in the work of redemption while we wait for the final act.

And one day, we trust, God will bring that final act of New Creation. He will call a stop to this course of time and re-create the world with no sin, suffering, or death. The Fall and its effects will be totally undone, and all agents of the Fall – both spiritual beings and humans – who lived by its pattern will be put away forever.

John puts it better than I could:

And I heard a loud voice from the throne saying, “Behold, the dwelling place of God is with man. He will dwell with them, and they will be his people, and God himself will be with them as their God. He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more, neither shall there be mourning, nor crying, nor pain anymore, for the former things have passed away.” (Revelation 21:3-4)

Putting the pieces together

How does this knowledge help us orient ourselves in a passage of Scripture?

Continuity …

Knowing where we are in the grand drama helps us see the continuity between our time and those past. Paul recounts parts of Israel’s wandering in the wilderness (Israel – Promised Land) to the Gentile Corinthians (Church), not because the Corinthians are supposed to set out into the wilderness, but because Israel’s story shows both God’s gracious provision and the danger of rebellion. He summarizes, “Now these things happened to [Israel] as an example, but they were written down for our instruction, on whom the end of the ages has come” (1 Corinthians 10:11).

In the stories from past acts, we see the same God we worship now, creating a new order and making a covenant with his people. We see the same fundamental problem of sin, and the same need for God to redeem the world and make a new creation. In each act of the drama, we see the same basic patterns that inform our life with God today. That’s why Paul could point to Israel’s failure to keep the covenant as a warning for the church today, and also why Jesus could say …

“Everything written about me in the Law of Moses and the Prophets and the Psalms [read: the Old Testament] must be fulfilled.” Then he opened their minds to understand the Scriptures, and said to them, “Thus it is written, that the Christ should suffer and on the third day rise from the dead, and that repentance for the forgiveness of sins should be proclaimed in his name to all nations, beginning from Jerusalem.” (Luke 24:44-47)

… without Collapse

At the same time, knowing where we are in the drama helps us keep from collapsing our eras into one another. There are differences in the terms of God’s covenants and the nature of his people, which is why we don’t keep kosher, worship in a Temple, or demand a Christian king. We can learn from all of those things – they can show us something about God’s nature, God’s work, or life with him – but they apply differently to us in the Church age of Christ the true Israel, the living Temple, and the reign of the Spirit instead of the Law.

To put that into practice, we might ask questions like:

What has God created in this act of the drama: what good world has he made and entrusted to his people in this passage?

What are the terms of God’s covenant in this passage, and how are his people keeping them, failing them, or struggling with them? How is our covenant similar to theirs?

How are the effects of the Fall impacting this passage – how are sin, death, or suffering present?

What kind of redemption is needed in this passage, or how is redemption being provided or promised? Where do I see God’s grace, wisdom, or salvation?

How does this passage contain hope? What new redemptive work are they looking for, and how is that fulfilled either in our act or the one to come?

Image: Jonah “rising” from the great fish with Jesus rising from the tomb, 15th century. From Wikimedia Commons.

[1] I prefer to think of this as a “drama with acts,” which I got from Kevin Vanhoozer, rather than a “story with chapters,” because a “drama” is both written by an author and carried out by performers, where a story is only written. “Drama” more naturally conveys the idea that we participate in the plot – that we have a role to play, though God is both the ultimate author and the main character.